When a call to peace provokes violence

The joint Israeli-Palestinian memorial ceremony is understandably controversial. Despite its resilience, the Gaza war has left less space for such endeavors

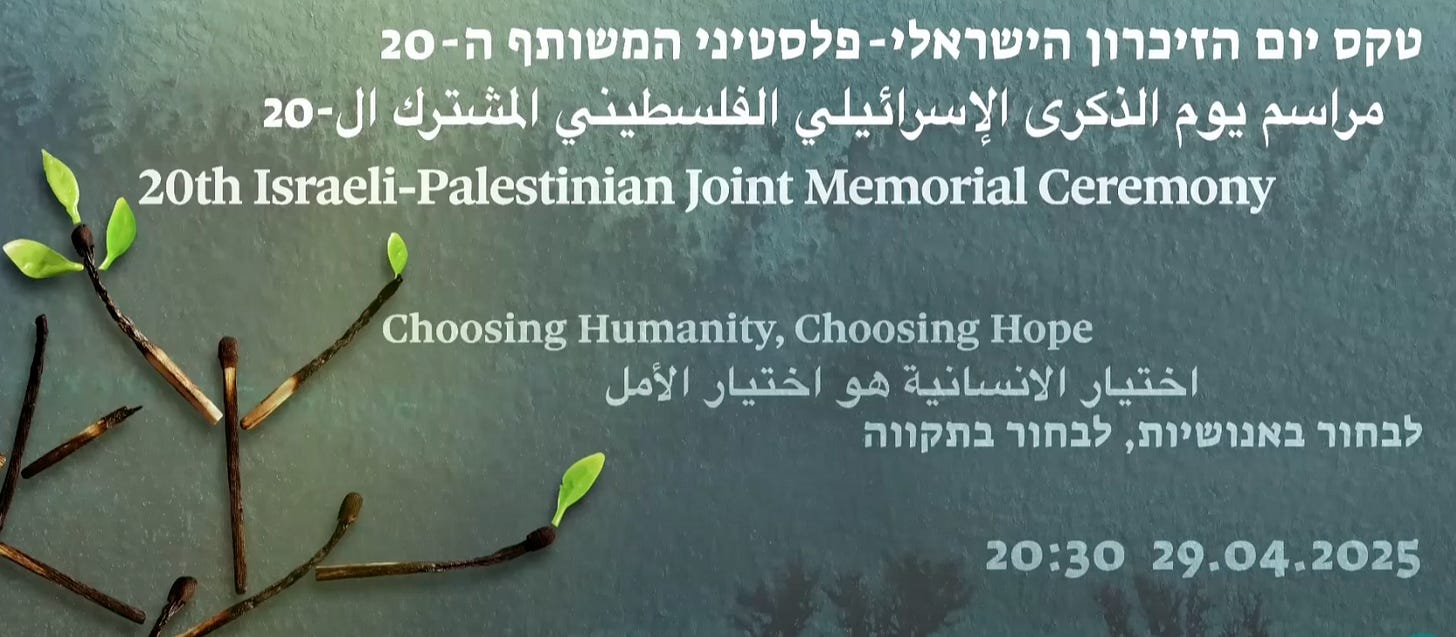

I’ve been walking around for several days with thoughts about the joint Israeli-Palestinian memorial ceremony that was held on Memorial Day eve last week. How it’s been held for 20 years now, about the content and about the violent reaction in Ra’anana, where a mob attacked a handful of people who had gathered at a synagogue to watch the ceremony remotely. How can such a small group be perceived as such a huge threat?

When conflict polarizes groups, each side tends to demand unity and to shun dissent. It is not a time for introspection. In this case, opponents of the joint Israeli-Palestinian memorial ceremony have been heckling its participants for two decades. The extreme violence of the October 7 atrocities made feelings more intense. Protesters equate any sympathy for Palestinian loss of life as support for terrorism and a threat to Israel.

Yet the protesters and the participants share something in common. Both their movements represent emergent phenomena resulting from extreme violence. Consistent with complexity science, even as conflict drives most group members to become increasingly convinced that violence is the only solution to end their own suffering, it also drives a smaller number to seek to build bridges to end mutual suffering.

The joint ceremony represents that rarer phenomenon of humans trying to hold the complexity and pain of both sides. They do it not only despite their own pain but also in the name of sparing their own people from future pain. I feel uplifted by seeing them share the sentiment with me that mutual recognition of that pain and commitment to ending it for both sides. Watching Israelis and Palestinians talking about peace as they stand side-by-side also makes me think of the course I developed last year on peace movements in the country.

It turns out that there have been individuals and groups advocating the path of peace almost uninterruptedly for nearly 120 years. They have represented a low level of randomness, advocating a different strategy than the mainstream Zionist movement and later Israel, remaining on the fringes for most of Israel’s history. I identify with them, even as I understand why the Zionist movement and Israel rejected them.

Choosing for peace is always the rarer choice because it makes one more vulnerable. We as humans don’t like being out of our comfort zone. As tribal-oriented, motivated reasoners, most people want to believe that their needs are justified, their cause is just and those who oppose their worldview are mistaken. Moreover, conflict drives the process of schismogenesis or othering, by which humans see their rivals in increasingly stark terms and mirror one another in these perceptions.

So, let me tell you about some of those people who prioritized building relationships and questioned the consequences of their movement’s or country’s actions. There was Yitzhak Epstein, the educator from Rosh Pinah, who warned the Zionist Congress in 1905 against dispossessing Arab peasants, stating, “The work that we give to an Arab will never be seen, in his eyes, as indemnity for the field that was taken from him; he will take the good but not forget the bad.” There was a group of Jews of Moroccan descent who, in 1914, founded a group called Hamagen to strengthen Arab-Jewish ties through literary clubs and promote understanding because they had witnessed the beginning of Arab fear of Jewish immigration. There was Brith Shalom, which included leaders like Henrietta Szold and Arthur Rubin, which declared in the 1920s: “We feel convinced that a Jewish National Home is only worthwhile if it is built upon a basis which provides for absolute justice for both Jew and Arab.”

Similar sentiments were echoed by groups like Kedma Mizraha, which emerged in response to the 1936 riots in Palestine, and Ihud, which promoted a binational state from the 1940s through the 1960s. After the Six-Day War, members of Matzpen warned that a prolonged occupation would eventually lead to terrorism and counter-terrorism, with innocent people making up the bulk of the victims. Then came Peace Now in the 1970s, which pushed for peace with Egypt and later against the counterproductive war in Lebanon.

Hopes for peace probably peaked in 1993 with the signing of the Oslo Accords, but the violence and frustrations that followed undermined broad public support for the overall process. The peace camp has never fully recovered from the Second Intifada that raged from 2000 to 2005.

And yet, more and different peace groups emerged from this cauldron. Whereas pre-Oslo peace groups were almost exclusively Jewish, Israelis and Palestinians now work together as equals; they include Combatants for Peace, Women Wage Peace, Bonot Alternativa, the Parents Circle-Family Forum and Standing Together to name a few. This trend is encouraging because Israelis and Palestinians are modeling coexistence rather than just imagining it. But it also feels threatening because it creates cognitive dissonance to anyone who mistrusts the Other. They resolve the dissonance by concluding that either their own people in these groups are traitors or the Others in these groups are acting deceptively, or both.

The relatively small size of the peace movement faces another challenge that further impedes its ability to influence Israeli and Palestinian society. Smallness means less complexity, including less diversity of opinions. Hence, the group may fail to see what looks like a good idea or message to share with the greater public lands quite differently outside the movement and may alienate potential recruits. This problem came to my attention when discussing the joint ceremony with my family. My son, who has a knack for observation, noted that the unbounded compassion expressed in the ceremony is shocking for people joining for the first time. He also pointed out that no soldiers were mentioned, which suggests the organizers have yet to include that complexity in the ceremony.

Of course, the mob in Ra’anana didn’t care at all about what was said at the ceremony. They were going to attack the ceremony viewers no matter what the content was. But that doesn’t mean that the content doesn’t matter. It’s just another part of the challenge the peace movement faces in expanding its appeal.

At the same time, the joint ceremony is a sign of the peace movement’s remarkable resilience in the face of mass violence. A recent poll found that 87% of peace activists did not consider abandoning their efforts in the wake of October 7 and the subsequent war. Such committed individuals include Palestinians who have lost dozens of family members in the war, like Ahmed Helou. Sadly, the war has greatly expanded the number of eligible members of the Parents Circle-Family Forum, which is made up of bereaved Israeli and Palestinian families. And the organization has indeed grown over the past year.

And so, ironically, this unending cycle of violence is going to continue generating new adherents to the peace movement. How it will end, there is no way of knowing. But in the meantime, I take comfort in the thought that community members continue to create hope in their own way and help mitigate the suffering of one another. As it is written in Pirkei Avoth (“Ethics of the Fathers”), “It is not upon you to finish the job, but neither are you free from shirking it.”

Thank you Steven for writing about peace. We need peace between Israelis and Palestinians, between Yemenis, between Iraqis, between Syrians, and so on.

Thank you .The Group named Combatants for Peace have joined two seemingly disparate terms toward defining a way forward, . Watching the memorial ceremony was quite moving. Would that the group’s social ~human ideals influence will grow, but having to meet in closed forums to remain safe seems to indicate intimidation. A fine “think” piece